Project + Writing

2013-2017

PhD by practice, Design Interactions, Royal College of Art.

Supervisors: Professor Sarah Teasley & Professor Anthony Dunne.

Found examples of the ubiquitous #dreamofbetter, which I collect and share on Instagram.

According to Nathaniel Wyeth, an engineer at Du Pont, it was late at night when he went to open the moulding machine in the lab. Expecting to find it empty, this time he discovered a crystal-clear plastic bottle. The search for the ultimate bottle to hold carbonated drinks was over. Patented in 1973, the polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plastic bottle proved to be safer, stronger, and lighter than the glass and other plastic bottles it replaced. The PET bottle was better; in fact, it was so much better that many of us have learnt to drink water every day from brand new plastic bottles, simultaneously creating corporate profit and an ecological horror story.

Design and technology helped to solve a particular problem for industry—light, strong, shatterproof vessels to sell fizzy drinks—and make something better by those measures. But is this better? Who is it better for? Who decides? The questions may seem obvious, but I’d never heard them asked so plainly.

Once I noticed the problem of better, I began to see it everywhere. Marketers use promises of better to sell everything from beer to chemicals, corporate social responsibility, financial tools, pizzas, and rival political ideologies. Advertisements, propaganda, policies, visions, and utopias are crafted by copywriters, politicians, designers—and even scientists—all promising us a better future. But better is not a universal good or a verified measure; it is imbued with politics and values. And better will not be delivered equally, if at all.

“What is better?”, “Whose better?”, and “Who decides?” are three seemingly simple questions with immense implications. In 2013, I returned to the Design Interactions department at London's Royal College of Art to explore better through practice and writing, finishing in November 2017. My thesis explores powerful dreams of better and how they have material effect, focusing on design and synthetic biology, and its links to Silicon Valley, and uses critical design to find new ways to ask better questions of those dreams. I regularly present "better" to design and technology audiences, asking them to question better, not just promise it. Better matters as the struggle for its meaning has returned to dominate global politics; meanwhile the few continue to define what is better for humanity, other species, and the future of our planet.

THESIS ABSTRACT

Designers, engineers, marketers, politicians, and scientists all craft motivating visions of better futures. In some of these, “better” will be delivered by science and technology; in others, the consumption of designed things will better us or the world. “Better” has become a contemporary version of progress, shed of some of its philosophical baggage. But better is not a universal good or a verified measure: it is imbued with politics and values. And better will not be delivered equally, if at all. “What is better?”, “Whose better?”, and “Who decides?” are questions with great implications for the way we live and hope to live.

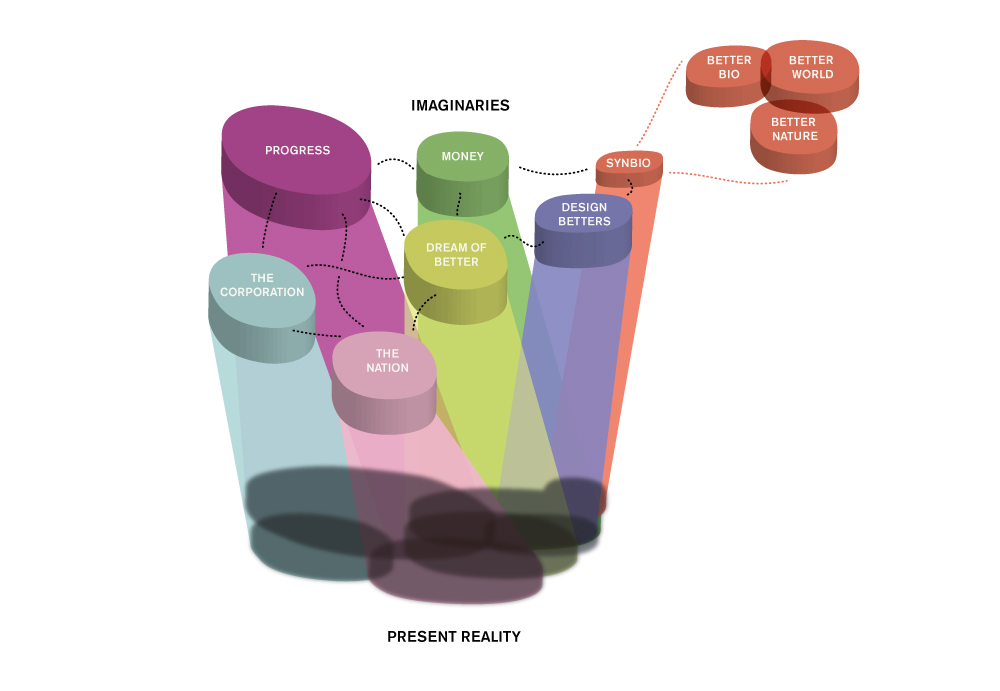

At a time when social, economic, and environmental conditions place in question the dominant paradigms of better defined by globalisation and technology, Better, a PhD by project, investigates some of the powerful dreams triggered by a banal word and develops critical design techniques to find new ways to ask better questions. This thesis contends that the “dream of better” is so influential in advanced technological societies that it is what science and technology studies scholars term a sociotechnical imaginary. The imaginary is used as a critical design tool to examine better, revealing links between design and the emerging technoscience of synthetic biology and other ideological spaces, like Silicon Valley. As a young field, synthetic biology offers a space to test and expand critical design’s potential.

Social imaginaries are shared fictions with material effects; collective imaginings that shape our experience of reality.

The practical research includes six critical design projects that engage with synthetic biology and its vision-making processes, using techniques from designed fictions to curation. The written thesis comprises six chapters informed throughout by commentary on the practice.

The first chapter looks at the influence of dominant concepts of better on design, separating design’s intrinsic optimism from engineering and market-led ideas of the optimum and optimisation. It situates critical design practice as an optimistic activity, seeking alternative meanings of better.

The next three chapters track how the imaginary of better has shaped synthetic biology and the field’s evolving culture of design. Meanings of better have proliferated since 1999, as synthetic biology’s visionaries promise to better biology, better the world, and even to better nature itself. But resistance has revealed the existence of alternative betters.

Chapter Five explores critical design’s examination of synthetic biology’s dreams of betters. Recognising the mutual colonisation of critical design and synthetic biology, which is contributing to the emerging platform of biodesign, the chapter discusses how navigating imaginaries can improve future critical practice. It encourages framing technoscience within society, rather than placing society downstream of it.

Chapter Six proposes that the social imaginary itself can be a critical design object. Designing “critical imaginaries” can open up our understanding of better, offering a process to reimagine the world. The critical imaginary is not a utopian effort to produce prescriptive visions of how the world ought to be. It is a heterotopian design technique to include diverse views and generate worlds that could be made, asking “what ought the world to be?”

Read Better here.

Found examples of the ubiquitous #dreamofbetter, which I collect and share on Instagram.

Social imaginaries are shared fictions with material effects; collective imaginings that shape our experience of reality.