2022

Curatorial essay for 'The Lost Rhino'. Published on the Natural History Museum website, 2022, to accompany 'The Lost Rhino' exhibition curated by Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg.

Edited by Jay Sullivan and Hannah Jones.

Installation image of The Substitute in 'The Lost Rhino' in the Jerwood Gallery, Natural History Museum, London, 2022.

Have you ever met a rhinoceros? Conjure one in your mind's eye. Outline its shape. Does it have one or two horns? Hairy ears? How big is it? Is its skin soft and thick or hard and leathery? Does it grunt and huff or is it silent? Can you see its chest heaving as it breathes? The rippling of its muscles as it turns? Is it moving or stock still, looking right back at you? Is its stare mournful, fierce or just blank?

Most of us have never met a wild, living, breathing rhino. You might have seen one plodding around a zoo enclosure or encountered a rhino-like shape, wrapped in preserved skin, a form frozen in time and locked in a glass case.

You might never have met a rhino, yet still, you can see it. Your rhino might be an imperfect, imaginary copy, assembled from images and ideas about rhinos, some 500 years old. But your rhino lives on in your mind.

Humans have killed, captured, shipped, traded, collected and marvelled at rhinos for thousands of years. As they disappear into biological history, why does this strange and far-away animal matter? What is a rhino to you?

Rhinos were among the earliest animals to be drawn. These rhinos in the Chauvet Cave in Ardèche, France, were depicted 36,000 years ago because of what they represent, not just to record their

WHAT IS A RHINO?

The Lost Rhino explores how the idea of an animal can become more powerful than the animal itself. For this installation, I've brought together four very different representations of the rhino in a contemporary cabinet of curiosities, spanning five centuries. Each is inescapably tinged with violence. Beating heart cells grown from the skin cells of a dead rhino, the most enduring image of the rhino and a rhino shot in 1893 to be displayed in the Museum's collection, stand alongside my own rhino placeholder, my artwork The Substitute.

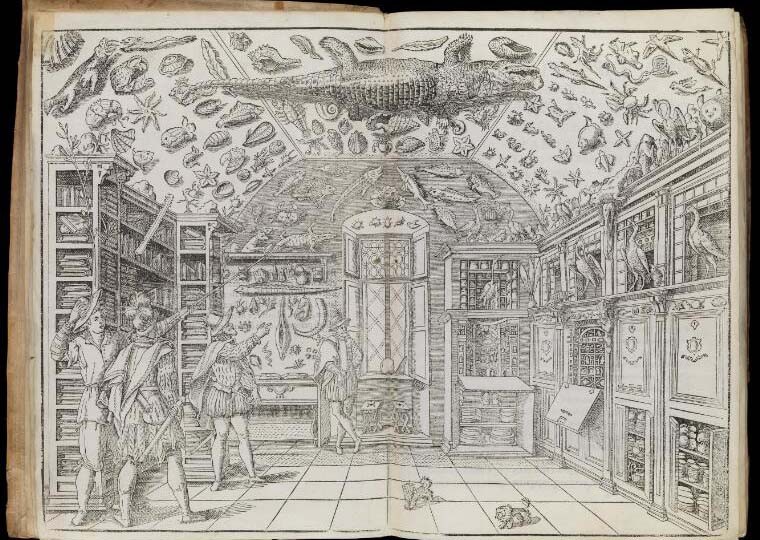

During the European Renaissance, cabinets of curiosity filled with natural wonders were used to build connections between objects and ideas. As scholars observed, measured and explained the natural world through science, 'exotic' animals like the rhino represented the unknown - and a world to be conquered and tamed. These early museums were used to show that humans were more powerful than nature and to elevate us above it.

But there are no rhinos in this cabinet. There are only rhino symbols, created by humans for humans. Each is alone in a box, divorced from its habitat. They are containers that hold our ideas about rhinos, but without a rhino's living interactions with the natural world, not one of them is a rhino. A rhino isn't an idea, it is an individual being with the right to exist, with no purpose except to be a rhino. Still, each of these objects is alive in its own way. And this liveliness matters.

The earliest known illustration of a natural history cabinet of curiosity. Dell'Historia Naturale by Ferrante Imperato, 1599.

THE IMMORTAL RHINO

On 20 March 2018, headlines announced the death of a rhino that humans called Sudan, the last male northern white rhinoceros, Ceratotherium simum cottoni. His loss condemned this southern African subspecies to extinction - he left behind two remaining rhinos, both female. Ami Vitale's devastating photograph of the dying animal, tenderly held by his caretaker, helped communicate the importance of this moment. We mourned. Then we moved on.

I first saw a northern white rhino's heartbeat two years after Sudan died. Over a video call from San Diego, Dr Oliver Ryder showed me a film of a pulsing sheet of myocardiocytes, the cells that make up the heart muscle. I was transfixed. Boxed into my screen, the grey, grainy microscopic cells looked like a rhino's flank, thumping with life. I had the uncanny sensation that if only I could zoom out, a complete, living rhino would come into view.

The Lost Rhino opens with the beating heart cells of Angalifu, the second-last male northern white rhino. He died in San Diego Zoo in December 2014. Dr Ryder and his colleague Dr Marisa Korody worked with samples of Angalifu's skin cells, 'rewinding' them into induced pluripotent stem cells - special cells that can become many other kinds of cells. Then they reprogrammed them to become heart muscle cells. After a few days multiplying, the cells spontaneously start to beat.

These cells might be the truest rhino in the exhibition: we can see life for ourselves. The cells contain the potential for life, yet they can never become a whole rhino. They are not Angalifu's heart, just a component of it. They are a living dead end - a scientific experiment for us to wonder at. While the endlessly looping film gives the appearance of immortality, in reality the cells die after a few days.

When Sudan died, reports softened the blow by explaining how his subspecies, destroyed by humans, might be brought back by humans. Professor Thomas Hildebrandt and the BioRescue Consortium had collected sperm from male northern white rhinos and planned to harvest eggs from the two surviving females, Sudan's daughter Najin and her daughter Fatu. After 10 rounds of egg collection, they injected individual sperm cells into each egg and as of September 2022, 22 northern white rhino embryos are in a freezer.

Meanwhile, Dr Oliver Ryder and his team are working in even newer territory. Since 1979, scientists at the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance have been saving cells from northern white rhinos for their Frozen Zoo. Forty years of scientific advance means they can now create stem cells, next they hope to transform these cells into egg and sperm cells to make embryos from a larger gene pool.

Both groups hope to implant embryos into female southern white rhinos, Ceratotherium simum simum, another endangered subspecies, who would act as surrogate mothers. However, it's not just the technology that is challenging. Firstly, there is the risk to endangered rhinos undergoing avoidable medical procedures. Next, as in human IVF, baby rhinos are not guaranteed, as not all embryos will grow successfully. And even if new rhinos are born, there might not be enough diversity to keep the population alive - a problem known as a 'genetic bottleneck'.

Promises of 'de-extinction' present an exquisite salve to our guilt of doing harm, or just doing nothing. But de-extinction is not quite what it seems. We think about DNA as an instruction manual, but biology is complex. Not all genes are switched on, and genes interact with each other and with the environment. You can't just print a rhino from its DNA.

A new rhino created through these technologies might genetically be a northern white, but would it be real? The northern white is - or was - the most social of all the rhino subspecies. Southern white rhinos have different behaviours. Isolated from its kin, its culture and its habitat, would a northern white raised by southern whites be true? Would it know how to puff, snort, threat, grouch, grunt, snarl, groan, pant, whine and squeak like its ancestors? It might look like a rhino, but it may only be a partial likeness.

Why would we look after this 'resurrected' rhino more than its forebears, which we hunted to extinction? This rhino might be better than having no rhino at all. It could help us understand rhinos better, help with conserving them and their ecosystems. But the animal also becomes a technological object, reduced to a placeholder for a lost species. We might value it more because it's a product of science. But its very existence sidesteps the causes of extinction. The survival of rhinos ultimately requires human, not technological reconstruction.

THE ENDURING RHINO

Five hundred years before Sudan's death, on 20 May 1515, a one-horned Indian rhino, Rhinoceros unicornis, was led off a ship in Lisbon. His captors called him Ganda - his Gujarati name - and he was the first rhino to arrive in Europe since Roman times. This precious gift was from the ruler of Gujarat to the Governor of Portuguese India, who sent him on to King Manuel I of Portugal. After his long sea journey from Cochin, Ganda was put into battle with an Indian elephant to prove their 'natural' rivalry, rumoured since Roman times. The elephant fled - the rhino didn't do much. Despite his reluctance to fight, Ganda's rarity made him a symbol of power and the King soon dispatched him to Rome as a gift to Pope Leo X.

Ganda died in chains in a shipwreck on the way, but like Sudan and Angalifu, he endures long after his death. The German artist Albrecht Dürer never saw Ganda in the flesh, but he read a letter describing him and probably saw an eyewitness sketch. Dürer drew his own picture, riddled with errors. He gave his fearsome rhino another horn on his neck, reptilian scales on his legs and protected him with armoured skin. The look in his eye is watchful and haunting.

A friend of Dürer, Hans Burgkmair the Elder, made his own more naturalistic image. But his didn’t convey the power of Dürer’s fantastic animal. It was Dürer’s drawing that was immortalised in a woodcut print, albeit with a few more adjustments: an even bigger horn on the rhino’s back, chin hairs, and a shorter body, making him even heftier. For a hundred years, Dürer’s artificial rhino was reproduced from the same wooden block, distributing its image far and wide.

The next two rhinos to arrive in Europe docked in 1579 and 1684; by 1810, only ten animals had arrived alive. In the absence of real rhinos, Dürer's became the model, endlessly copied - uncredited - in accounts of nature until the middle of the eighteenth century. The Natural History Museum's collection contains many descendants of Dürer's rhino, four of which are in the installation. One of the most extraordinary is the Historiae Animalium, published in 1551. The Swiss naturalist Conrad Gesner copied Dürer's print as he attempted to catalogue everything written about all known animals, including the unicorn (suspected of being the rhino, or rather, the rhino was the ugly reality of the unicorn). In 1600, the Flemish-German engraver Theodor de Bry published a series of books recounting European journeys to Africa and Asia, replicating Dürer's rhino. A century later, Dürer's rhino was still the model, appearing in Wenceslaus Hollar's 1700 catalogue of nature and in Michael Bernhard Valentini's 1704 book Museum Museorum about early private museums.

As colonial expansion delivered more rhinos to captivate Europeans, it became clear that Dürer's rhino was more a product of imagination than scientific observation. Still, his version continued to proliferate. In the caption on his original woodcut, Dürer describes the creature as 'quick, alert and crafty'. He fixed the essence of what a rhino is in the modern human mind. Capturing its brutish strength, its intelligence but also its unknowability, he cemented the rhino as a vessel of both animal and human power.

THE TRANSFORMING RHINO

In laboratories around the world, scientists are trying to construct life from scratch, from its biochemical ingredients to programming artificial intelligence (AI). Only by building life can they truly understand it. Modern humans appear to be preoccupied with creating new life forms while they destroy existing ones.

After Sudan's death, I decided to create my own rhino to explore this paradox. Grunting and stomping as it comes to life, the third rhino in the installation is The Substitute (2019). This video projection shows a life-sized northern white rhinoceros - around 1.8m to the shoulder and 3.75m nose to tail - roaming around an empty white room, transforming from a pixelated mass into a high-resolution facsimile. Finally, the rhino catches your eye, then disappears without warning. The cycle repeats infinitely.

The Substitute might look and sound like a rhino, but it's another imperfect copy. Its movements and sounds are copied from footage by Dr Richard Policht documenting the last eight northern white rhinos, including Sudan, in the early 2000s, then held at Dvůr Králové Zoo in what is today the Czech Republic. The Substitute is a collection of many individuals, male and female, out of context.

The path it takes is not its own either. A few weeks after Sudan's death, the AI company DeepMind announced it had created an artificial agent - an entity that interacts with its environment autonomously - that had learned to navigate its way around a virtual room. Our mammal brains have evolved hexagonal patterns of neurons called grid cells. These fire as we map the world around us. The agent found the same solution. I was fascinated by this seeming leap towards intelligence: existing in space is a sign that you do indeed exist. The next step from 'I am here!' is being aware of your existence and communicating it: 'Here I am!'

DeepMind let me use their experiment to create routes for The Substitute to tread. In the artwork, a second projection shows the agent exploring, learning its place in its world. On the right, we see coloured pixels showing the development of its grid cells. Like Ganda performing in battle to prove his rhino-ness, The Substitute performs the role of the artificial agent as it develops. We value this rhino because it's an artificial construction that showcases our ingenuity. Creating life tells us more about ourselves and what we value than about the rhino.

The Substitute is the closest you might ever get to a rhino. Despite its imperfections, its life force transforms us. In his book Why Look at Animals?, the art historian John Berger explores how we become aware of ourselves as we return the look of an animal. The Substitute begins as the object of our gaze, but the roles flip as the rhino catches our eye. Suddenly, we are subjected to its stare. We're the animal on the spot, forced to recognise the wild in ourselves. Before we can react, the rhino is gone.

THE SHAPE OF THE RHINO

Ensconced in a surreal pink box, the exhibition ends with a taxidermy southern white rhino. The only real rhino here is not really a rhino, but a rhino's skin, stretched over a padded armature. Even its horn is fake - criminals even hack the real ones off museum specimens. This rhino is another paradox: long dead but living on.

When we look at taxidermy, it's easy to see a model and forget that this was once a living individual. In 1893, Robert Thorne Coryndon, later the Governor of Uganda and then Kenya, shot this rhino in Mashonaland - near present-day Harare, Zimbabwe. Coryndon wrote a harrowing account of the hunt and the contradiction of its new life in the museum. With a logic that seems extraordinary today, he explained that as gun technology improved, rhinos were disappearing in the region, and thus more should be killed for museums in Europe and America. That way rhinos could still be studied even after they went extinct. This ghostly rhino stands in for the brutality colonialism inflicted on humans and other species, but its death is also part of a much longer, complicated history of hunting rhinos by both Indigenous peoples and Europeans for meat and trophies.

Many of the ideas we have about rhinos are cultural, not scientific. Despite their reputation for thundering violence, their fragility against a gun proved for some trophy hunters that they were indeed a stupid, prehistoric relic of old nature that deserved to die out. Coryndon, for all his flaws, defended the rhino's reputation: if you were shot at, wouldn't you charge in anger too?

One hundred and thirty years ago, this rhino took on a new life as a scientific object, supporting the survival of others that have lived since. But even as a specimen filled with useful data from its DNA to its vital statistics, it still can't give the complete picture of the living, wild animal. The taxidermy rhino underlines the importance of conservation rather than banking on unproven technology to replace what is lost.

The rhino's immortal heart, its enduring image, its transformative stare, its preserved shape: in this exhibition, ephemeral nature is transformed into artefacts with a life of their own. Each gives us the sensation of a rhino, yet they don't add up to a living whole. A representation is not reality.

Since Ganda stepped off the boat in Lisbon, the rhino has represented our desire to emancipate ourselves from nature. In 1515, the first mass-produced image of the rhino sparked fascination and led to their destruction. Today, their images are used to appeal to us to preserve them, but they also numb us. If they can live on in our imagination, does it matter if the real thing no longer exists? Will we even notice their absence? The tragedy of the image is that it becomes more powerful than the rhino itself. Its image has got in its way: the rhino is strong, but like all life, it's also fragile. If the rhino is the emblem of how we treat nature, it's also a symbol that we could do otherwise.

We think of utopia as the perfect place, but utopia means 'no place'. It's also a place of despair because it can only exist in our minds. These rhinos are objects of despair, but they are also hopeful. They are utopian animals: each contains the possibility of a living rhino and with it, the hope of reconciliation between humans and nature. They hint at a world that could be otherwise. A world where rhinos flourish. That would be the best of all possible worlds.

The Lost Rhino moves scientific artefacts into the realm of the imagination. I hope that as you step back into the Museum's collections you will see them differently too: not as an archive of lost animals, but as a place of possibility that things - and most importantly we - could be otherwise. Why does this strange and far-away animal matter? Simply, the rhino cannot exist with us, but it will be entirely lost without us.

Installation image of The Substitute in 'The Lost Rhino' in the Jerwood Gallery, Natural History Museum, London, 2022.

Rhinos were among the earliest animals to be drawn. These rhinos in the Chauvet Cave in Ardèche, France, were depicted 36,000 years ago because of what they represent, not just to record their

The earliest known illustration of a natural history cabinet of curiosity. Dell'Historia Naturale by Ferrante Imperato, 1599.